As this blog goes live, we have experienced an extraordinary weather year across the UK, and the impact on farming and growing has been profound. February and March saw record rainfall across most of the country, followed by some drier spells and then continued rain in places. The net result has been one of the most challenging springs for years, which is such a crucial time in the UK farming calendar. Late spring and early summer has been very variable, according to which part of the country you are.

Rewind to summer 2023 and June was considered to be the hottest June ever in UK weather records, followed by another hot spell in September. Yet in between, July and August were unsettled, with two major storms. Mild, stormy and wet spells were the continuing theme for the latter part of the year.

Everyone in farming and growing understands the critical effect that weather plays in the annual cycle of producing food, managing land, and the financial health of farm businesses. It is clear that weather patterns and the climate are becoming more unpredictable, creating significant impacts for farms, land and food. How do farmers and growers plan for the future with climate extremes becoming the norm?

The outlook

Met Office predictions for the trends in UK weather patterns over the next 30 years or so will include:

- Warmer and wetter winters

- Hotter and drier summers

- More frequent and intense weather extremes

This is happening now, but the knock on impacts are sometimes harder to predict, for example:

- Unpredictable weather patterns make all sorts of farming operations – from silage cutting, potato planting, arable drilling to crop harvest far more difficult to plan

- Significant variations in crop and animal health due to stress factors

- Uncertainty in business planning and financial returns

- Cumulative impacts that compound to present challenges – such as shorter windows to plant, changing pest and disease pressures, international market changes, etc.

In short there are many climatic challenges facing farmers, growers and the wider food sector, and many of them are simply not known yet. We’re all learning in this process and no one has all the answers. Climate adaptation is every bit as important as climate mitigation in the farming world, and sometimes the answers for both mitigation and adaptation can be the same. Weatherproofing your farm should be a priority for all farmers and growers.

Short to medium term solutions

So what can you as a farmer or grower do about it? There are things out of our control – the location of our farms (well, unless you’re up for moving!) and the weather systems we receive, but there are plenty of things that can be done to adapt. We’ll look at our top five actions

- Soil health

- Water management

- Diversity in the business

- Knowledge of the trends

- Investment in the future

Soil underpins everything we do in farming, and a healthy soil can be incredibly resilient in terms of water management, soil health and structure. Increasing organic matter content, enhancing soil biology and minimising cultivation and compaction can have massive benefits.

Water is crucial for all plant growth, but having too much or too little can massively affect all crops, from grass to cereals and vegetables. A soil with good structure and good organic matter levels can help buffer against both flood and drought conditions. However, having plenty of available water for irrigation when needed can be essential for crops like vegetables and fruit. Most farms can improve their water storage capacity, harvest more rain water and implement efficient irrigation systems.

Diversity of enterprises on the farm will help guard against the danger of having all your eggs in one basket. Inevitably some crops or products do better than others in different years. This might mean a range of crop types, genetic diversity within a particular crop, or branching out to try different breeds of plants and livestock. A biodiverse farm can also help regulate extreme weather events, even changing the micro climate of a farm.

Knowledge of the farmer or grower is one of the most powerful tools. Understanding what a changing climate might look like for the farm, and planning ahead is vital to build resilience and guard against risks from extreme weather.

Investment in the future could be the key to business resilience. For example, identifying that the farming system would benefit from more trees, water storage, different cultivation equipment, livestock sheds, etc. This forward planning and investment should be strongly considered if and when finances allow. Grants are also available, such as those offered by Defra.

Longer term solutions

At Farm Carbon Toolkit (FCT) we work with businesses every day to create Carbon Action Plans, where we recommend short, medium and long term solutions; Climate Adaptation Plans should be seen in a similar way. Having said that, making a long term plan to cut carbon is much easier in its aim – to cut net carbon emissions to zero or beyond. But with climate adaptation plans – what is the aim?

That question is hard to answer as the climate of the future is uncertain. But what do we know is true? Well, the climate we’re used to is changing , as are weather patterns. Predictions are currently largely coming to pass, and so that gives us some guidance. Bearing in mind they are just predictions, one thing is certain – farms need to be resilient, adaptable and well prepared. It is likely the future will not look much like the past.

Change can be very challenging, especially in businesses like farming which are inherently long term. Embracing change can be difficult for many reasons – resources, money, land capability, mindset, tradition and much more. But burying our heads in the sand is also not viable – this is difficult, but it is happening!

Here are some areas to consider:

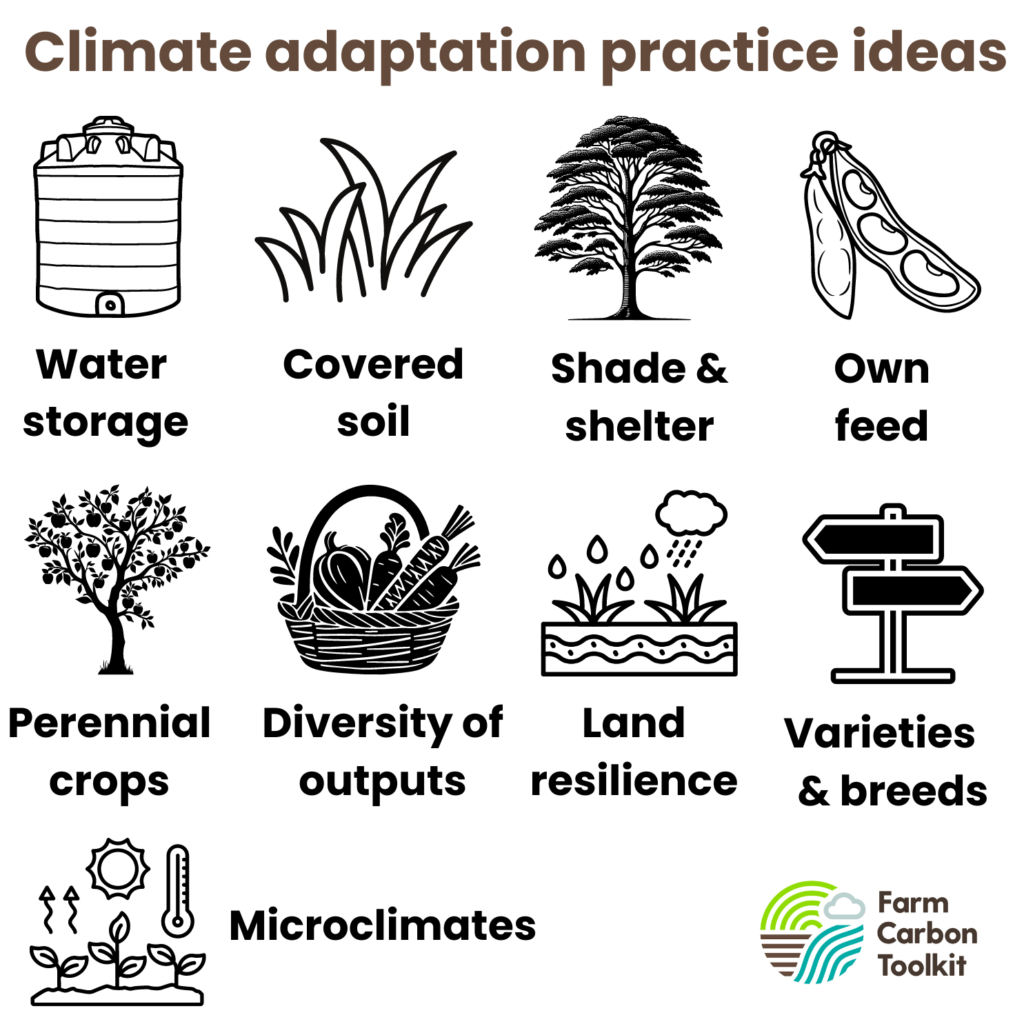

- Cultivated soils are particularly vulnerable to soil erosion, drought and flooding. Moving towards reduced cultivation and better soil that is permanently covered will build resilience

- Adapting land use to be more resilient to intense rainfall events

- Livestock can be very vulnerable to heat and extreme weather. Providing shade and shelter can help reduce the impacts on animals

- Animal feed supply can be impacted significantly by weather, in terms of price, availability and quality. Are there ways to boost feed self-sufficiency and feedstock resilience for the farm?

- Perennial crops tend to be more resilient than annual crops. Opportunities might exist to shift cropping systems to build resilience

- Diversity of farm outputs may help to reduce the number of “eggs in one basket” and spread climate-related risks

- Microclimates can help farms to adapt. Trees, hedges and agroforestry can help to provide shade, manage water, and shelter from storms, as well as offering alternative income streams

- Water storage can improve in quantity and ability to deliver water to crops, in combination with soils that have improved water holding capacity.

- Varieties and breeds that are adapted to your local soils and climate may do better than others, for example population wheat. Local seed breeding is a skill that has largely been lost to most farmers and growers.

Whatever future path is chosen by farmers looking to adapt to a changing climate, two themes are clear. Firstly, that no one solution will work and a pathway should be holistic. Secondly, those plans should be adaptable and may well have to change. The future is uncertain, but a resilient business that has planned ahead has a better chance in weathering future storms. FCT can help you in that planning.

Helping you

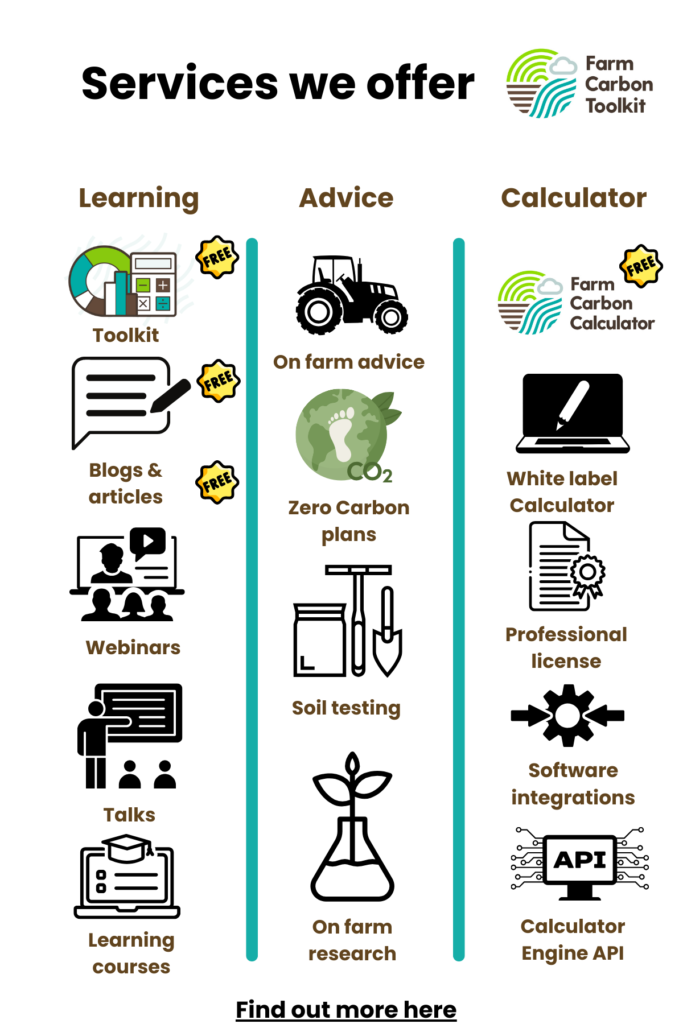

An increased focus for us at Farm Carbon Toolkit will be to help you with services, tools, techniques and insights to adapt to a changing climate. We have over 15 years experience in helping farmers and growers to measure, understand and reduce their carbon footprint. We have a range of services, and a team of experts who really understand farming. Increasingly we will be doing more to help you both reduce your carbon footprint, and adapt to a changing climate.

Recent Comments