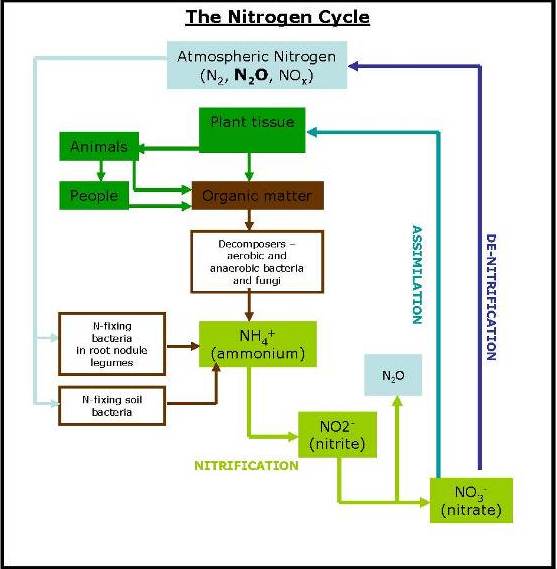

The movement of Nitrogen in the soil gives rise to Nitrous Oxide (N2O) emissions. There has been an increase in nitrous oxide emissions from 5.6 Tg Nitrogen per year in the 1980s to 7.3 Tg Nitrogen per year between 2013-16, of which agriculture was responsible for 87% of this direct rise. Nitrous oxide arises from soils primarily via the two biological pathways of nitrification and denitrification, as displayed below.

The Nitrogen Cycle

How is N2O produced?

As in the carbon cycle, in the nitrogen (N) cycle the vast majority, 98% of the earth’s nitrogen, is locked away in the lithosphere, 2% is in the atmosphere (the air we breathe is 78% N gas) and only 0.2% in the soil. It is this 0.2% that is the primary driver of the biochemical nitrogen cycle, and it is the movements of nitrogen in the soil that can give rise to N2O emissions.

Nitrous oxide emissions from the soil result from biological and chemical processes carried out by microbes that use inorganic nitrogen compounds (ammonium, nitrite and nitrate). The processes that release nitrous oxide include microbial nitrification in aerobic soils, denitrification of nitrate in anaerobic soils. Denitrification can result in the release of nitrogen gas (N2) as well as N2O and as these are biological processes the rate at which this occurs is dependent on a number of factors.

A significant factor in the production of N2O is the availability of nitrate (NO3) for the denitrifying bacteria to reduce. Plants take up N from the soil as ammonium, nitrites or nitrates, with the majority as nitrate. NO3 is mineralised from the soil organic matter and is also added to soil as ammonium nitrate fertilizer. Some of the NO2 will be rapidly taken up by plant growth, some will be immobilised into the SOM, some may be leached out of the soil and some is likely to be denitrified. If there is too much NO3 for the plants to take up it is liable to denitrification and leaching.

Why is it important?

Emissions from UK soils as N2O are less significant than CO2, despite N2O being 265 times more powerful a GHG than CO2.

N2O emissions can be seen as a tiny but significant part of soil make-up, due to its huge carbon equivalent, as well as being essential for biological processes that enable soil microbes to flourish.

The soil nitrogen is present either as inorganic nitrogen (available for plant uptake) or organically bound nitrogen in the soil organic matter. In general over 90% of all soil nitrogen is in organically bound in the SOM. The majority is in the ‘active’ and ‘stable’ pools, and is mineralised into inorganic nitrogen and made available for plant uptake, or loss from the soil, by the action of soil micro-organisms oxidising the SOM.

Minimising Emissions

The vast majority of denitrifying bacteria require relatively anaerobic conditions. Soils need to have a field capacity of over 60% for dentification to occur and so improving soil structure and adequate drainage can be significant factors in reducing N2O emissions. This can be done by adopting methods such as reduced tillage as well as introducing legume crops in to the rotation which will provide more nitrogen in the form of organic matter which will be released more slowly and used effectively by growing plants (Government of Western Australia, 2018).

Temperature, available carbon and pH are also important variables – the dentrifying bacteria will be most active in warmer soil conditions with higher SOM (and available soil carbon and energy) and with a pH of 7.0 – 8.0.